Student Voice at Seaview High School: reframing pedagogy and building school culture

28th June 2017

Two earlier posts have highlighted the importance of student voice in improving student achievement. The 2 schools involved were Craigmore High School and Streaky Bay Area School .

At Streaky Bay AS the focus on student voice grew from a survey of senior school students to uncover the support students needed to improve their learning. The students identified both the areas they themselves needed to address and also the areas where they wanted teacher support. It was this second area that opened the door to students making judgment calls on how their teachers taught them and how the teaching could be developed and modified to support them as learners. As well as the specifics of class room pedagogy, the focus fell on on curriculum design and assessment. The focus on student voice in the area of learning also extended to other areas of daily school life, from the pastoral care program through to subject delivery options, a specific concern in country schools. There was some external research support for the work at Streaky Bay but, overall, the school worked from an individual analysis of its own unique needs. Arguably, the relatively small size of the school facilitated its approach.

The Craigmore experience drew far more on an external research component. It was one of the TfEL (Teaching for Effective Learning) Pilot schools and as such it had access to additional teaching resources and research. The project occurred within the particular pedagogical framework of TfEL. At the same time, its focus on student involvement in teacher pedagogy and more specifically, assessment, produced positive outcomes similar to those of the Streaky Bay experience.

Seaview High School 2013-2017

The experience of Seaview High School over the past 4+ years is yet further proof that the deliberate and supported involvement of students in the school’s teaching program will improve levels of student achievement. The following case-study also demonstrates the potential of student voice to enhance school culture. Like Craigmore, Seaview was another of the TfEL Pilot schools.

At Seaview, the school’s new principal (Penny Tranter) was, from the start, concerned to improve what she saw as a problematic school culture. To her ‘new’ eyes, there was too much ‘excusatory’ language – students won’t be able to do this; there’s no point in having unrealistic expectations. Student achievement data which the principal analysed was being rationalised away with the same thinking. Specific achievement data represented clear scope for improvement but there was an obvious impasse if, as some staff believed, the fundamental problem lay with the students themselves. The new principal also noted that this ‘distance’ between the students and staff was also evident in other areas, including student behaviour management.

The first initiative of the principal was to review the school’s student behaviour policy. Within this review, she ensured that the students themselves were actively involved. The outcome was a negotiated classroom (behaviour) agreement, within mandated whole-school requirements. The next step – there was obvious overlap between the two – was to challenge commonly held assumptions about the students’ learning. The key to this approach was, again, to insist that the students themselves had a voice. There were 2 underpinning beliefs at work. One was that students, as participants in the teaching-learning dynamic, enjoyed a fundamental right to have their voice heard. The second was that the students’ assessment of the teaching they received represented a critical means of improving the teaching itself and, thereby, student outcomes.

There were other developments that also highlighted this focus on the relationship between student voice and pedagogy. The 2 most significant were the work on the Australian Curriculum and the Australian Teacher Performance and Development Framework (2012). Themes common to both of these were the focus on shared and collaborative curriculum design and also the formal use of performance feedback – against closely defined standards – from self, peers and, most importantly, students. With staff support, the school was able to build a professional development program round these national initiatives and both, in turn, legitimised the student-centred approach. One important practice employed at the time was to video tape students talking about when and how they learned best and using this material to open staff PD on the whole issue of student feedback.

At this time, the school was also promoting the use of the TfEL framework. TfEL gave a theoretical basis for looking closely at task design and the use of achievement standards to help students understand the expectations. It also reinforced the need to seek and then incorporate student feedback in the teaching dynamic. The TfEL Compass was to prove particularly useful in this regard. Students began to articulate their beliefs. In response to open-ended question such as:

how do you learn best?

what makes learning exciting?

what would you do if you had more voice in learning?

They were able to articulate their preferred positions:

we learn best when the learning is personalised and connected to us

we learn best when we can work in groups and talk about our learning with peers

we need to be able to negotiate, self-direct and self-regulate our learning

The student beliefs and experiences identified at Seaview within the TfEL work aligned strongly with findings from across the system and State.

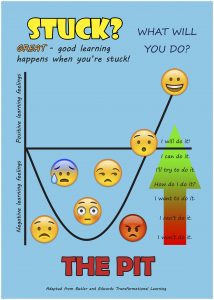

Importantly, while there was an obvious focus on challenging long-held assumptions about student performance and potential, the school was, at the same time, raising expectations about the level at which the students needed to work. There was always the recognition that the students themselves needed to be pushed beyond their performance ’comfort zone’ and have their own negative assumptions challenged. In short, the whole school culture, affecting both staff and student preconceptions, needed to be challenged.

In 2014, Seaview’s background work with TfEL helped it become another of the TfEL Pilot Schools and, critically, the principal considers that this involvement over the next 3 years provided the means to consolidate the change in school culture. The appointment of a TfEL Pilot leader – Sarah Millar – was to support both the school and the wider partnership (Marion Coast Partnership). Her work over the next 3 years was critical to the success of the project. The principal argues that the worth of the school’s involvement in the state-wide TeFL project was considerable. It gave the school much needed and significant additional human resources, both in terms of time and expertise. It offered the pedagogical framework and the shared language for school improvement, with a clear focus on teaching improvement and the role of student voice within this improvement. It gave the school access to highly valuable and relevant external resources and research. It made it possible for the school to work within a very productive relationship with all its Partnership primary schools.

Within the pilot program over the next few years, the school was able to develop a professional learning program for staff that focused on giving students the skills to extend their thinking, and also better understand themselves as active learners. There was work on the inquiry approach known as ‘Non-Googleable Questions’. There was also the work of Carol Dweck [see for example] with its focus on the importance of students moving from fixed to growth mindsets. Similarly, the work of Joan Dalton – 4 categories of 21st Century Skills – was important. Moreover, within the project there was a specific emphasis on Maths and Numeracy and so there was a focus on recent developments in the teaching of Maths. Here the work of Dan Meyer – 3 Act Maths – was very important. Meyer [see for example] claims that too often in conventional maths teaching students display:

lack of initiative

lack of perseverance

lack of retention

aversion to word problems

eagerness for formula

In his approach he is keen to:

use multimedia

encourage student intuition

ask the shortest question that can be asked; the more specific questions come out in later conversation/group work

let the students build the problem (formulating the question is the critical skill)

be less helpful

He aims to extend students’ intuition by tackling real world (Maths) problems. Meyer personally delivered PD to staff and students from the school.

Overall, the PD program at Seaview was designed around teachers helping students to better understand themselves as learners – resilient learners – and be able to identify and describe the teaching and learning that worked for them. It was also intended to place increased intellectual pressure on the students so that they could ‘stretch’ and ‘deepen’ their thinking. Students also needed to develop essential research skills and a broad based inquiry-approach to learning. In terms of changing the students’ own attitudes to learning, there was also the work to help students develop a ‘growth mindset’ and appreciate how important it was for both their learning and personal development. In all of this, the clear intention was to place the student at the centre of the teaching dynamic and pay close attention to what they said about how best their learning could be supported. Further, Student Voice was extended beyond teaching in the specific classroom and, for example, in 2014 a group of students conducted an audit of student voice across the whole school, with the results presented to both staff and students.

School change of this order can pose significant challenges. Some staff can feel threatened by the idea of student feedback on their teaching. In their view there is little if any value in the practice and, moreover, it can represent a direct threat to their authority. They believe that students cannot be ‘non-judgmental’ and will try to ‘exploit’ the situation. As well, from this defensive perspective, the fundamental problem of student achievement lies not with the teacher but with the students themselves.

In addition, there is always the question of pressure on the staff. Obviously, changes to conventional practice – even when such changes promote improved student achievement – can be perceived by staff directly involved as additional sources of unwanted pressure. This was particularly so at the time, because of the system-wide demands placed on teachers in areas such as the Australian Curriculum and performance development generally. To staff already under such pressure, the school’s particular focus on student voice – even though it was an integral part of the broader system-wide demands – appeared to represent even more pressure.The principal also noted that some staff did not see, at least initially, the connectedness between the several themes developed in the professional development program. They needed to see the entirety and integrity of the whole program. For example, the focus on growth mindsets was not an isolated pursuit but an integral component in the overall drive to change students’ attitudes to their learning and thereby lift performance.

However, it was not just the concerns of staff because some students were also challenged by the changes to pedagogy, and the expectations underpinning the changes. They had no problem with participation in student voice exercises or articulating what they preferred in terms of their learning; but some found unsettling the shift to inquiry-based learning, with the extra demands which were placed on them. For example, early trials with classes indicated that some students found the idea of ’stretch thinking’ – via the likes of Non Googleable Questions – difficult. They were not prepared to embrace, automatically or naturally, a form of teaching that forced more responsibility for learning back on to them and removed a lot of the conventional ’supports’. They wanted the teacher to be, ‘on call’ as soon as ‘they got stuck’ and ‘provide them with the ‘answer’. The shift from ‘passive’ to ‘active’ learner was not necessarily embraced by all. Some students who in the past had been capable were seen to disengage. The same student concerns emerged specifically in relation to Maths where not every student responded positively to the new ‘Mathematics by Inquiry’ approach. Not every teacher can become – and certainly not overnight – a Dan Meyer; and nor will every student shift effortlessly from the supported learning environment of text book and formula to the more ‘risky’ world of problem solving and reasoning proficiencies, particularly if there is a lack of relevant resources.

While there there was broad support from staff, and students, for pedagogical change driven by student voice and a commitment to lift student achievement, the school needed to proceed carefully making sure that both staff and students could be supported. There needed to be a lot of supportive leadership from the principal and leadership team and the staff had to see the principal’s commitment to the work. One effective practice was the use of volunteer staff who were prepared to step outside their ‘comfort zones’ and trial new approaches. They would then present their findings and experiences to the whole staff. Commonly this work was video-taped so that it could be shared more widely. The ‘showcase’ was used frequently in professional learning sessions. Staff were prepared and keen to support each other. They could see cultural change occurring in the school. It was also significant that the principal herself delivered much of the staff professional development, particularly in the beginning.

There was also a clear description of ‘non-negotiables’: levels of student achievement had to improve, particularly at the top end; teachers had to be more explicit in their teaching, about both the required outcomes and the processes to achieve them; there had to be a focus on using the achievement standards to support student learning; the school had to develop a culture of learning in which students understood and practised their own rights and responsibilities as active learners; inquiry-based pedagogy was to be pursued. And behind all of these there was the given that student voice as well as being a key component in the broader school culture was also a specific requirement in teachers’ performance development. Additionally, student voice was extended across the school, beyond the teaching-learning dynamic.

After 3 plus years of the school’s efforts, the principal considers that there is now a comprehensive range of positive indicators to demonstrate the success at Seaview. In terms of data related specifically to student achievement, results in both NAPLAN and SACE have improved. The number of students successfully completing SACE has also improved. Related to this ‘academic’ improvement, both attendance and school retention data have also improved. Similarly, there has been an ongoing improvement in student behaviour management data. At the broader level, there has been a very significant growth in overall student enrolments in the school.

There are other significant indicators. For example, the school has invested significantly in improving the quality of basic student facilities, including toilets. Similarly, there has been an extension of the range of school interests and activities for students. Student work is featured prominently and proudly throughout the school. All such efforts represent, in tangible form, the intention to place the student at the core of the school’s life. The principal stated that the students know that they are the centre of the school’s business and they respond accordingly.

Significantly, because of the partnership dimension to the TfEL project, the improvements at Seaview, in terms of the elevated status of student voice, the focus on supporting student learning and the deliberate efforts to extend student learning and achievement, have all been reflected in the local primary schools. One result of this has been that many primary students transition to Seaview already familiar with the school’s essential culture. For example, students come from primary school with the expectation that they will, as a matter of course, be able to comment, in a non-judgmental way, on the quality of teaching they experience in the classroom.

In the principal’s view there has been a profound shift in school culture at Seaview. She notes the cultural shift in the school’s approach to teaching and learning, and beyond:

The school is more inclusive. Students are now clearly positioned at the centre of all we do. They are active participants in their learning. Students can articulate clearly about learning and about themselves as learners. They know what ‘stretch thinking’ feels like and they are learning to expect it and to demand it. Teachers understand the impact of effective pedagogy on student outcomes. They are far more enthusiastic about sharing their practice and reflections. They see the value of the TfEL framework. Staff and students have developed and share a common language about learning. Middle managers are now integral to leading improvement. And, most importantly, right across the school student voice is authentic, powerful and influential.

This account does not cover the full story of Seaview’s journey over the past few years. There are other factors and programs that have had an impact. For example, the tracking and monitoring strategies developed with the SACE improvement strategy. However the story of Seaview over the past few years does demonstrate, once again, just how powerful the deliberate focus on student voice can be as the driver of change, in both the education program and the broader culture of the whole school.

Contact

Principal, Penny Tranter : [email protected]